Part One

In the fifth paragraph of Cicero’s On Duties, he begins with these words:

Atque haec quidem quaestio communis est omnium philosophorum; quis est enim, qui nullis officii praeceptis tradendis philosophum se audeat dicere?

Yet, this investigation is indeed common for all philosophers; for who would dare call themself a philosopher, who left behind no teachings of duty?1

This one sentence encapsulates everything that Cicero sets out to do in his famous treatise on duties.

This series will be in three parts covering the three books (long chapters) of On Duties. As I read through the book in its entirety, I will publish another essay concerning each book. There was a lot to unpack in the first book, so I’m interested to get my thoughts organized.

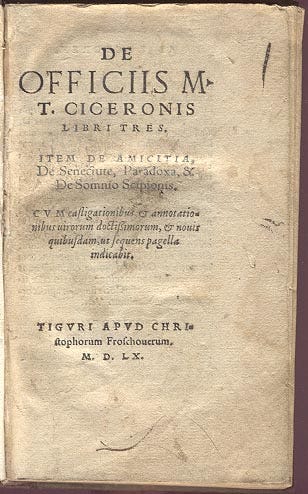

Cicero’s On Duties has been a classic in some sense since it was published posthumously in 44 BC. As a treatise written to his son (who was studying in Athens at the time) it has a personal feel to it that is lacking in some of his more “polished” works. The Latin is still recognizably Ciceronian, however, its prose is more quotidian, if such an adjective could ever be used to describe the famous Roman orator’s writing.

What is more, the book has been praised throughout the centuries, whether it be Christians, Pagans, Stoics, Deists, or any other living creed. What better acclaim could a book receive from such a contentious lot of beliefs? Further, this was an important philosophical book for the Founding Fathers, including Thomas Jefferson. When I saw this book on Jefferson’s booklist years ago, I knew I wanted to read it; but foolish as I was, I waited until I could read it in Latin first, which kept me from gaining its profound wisdom until now.

Though I confess I haven’t read much modern philosophy (besides Macintyre), I do wonder how most modern day philosophers broach the subject of duty, or if they do at all. My guess would be they don’t, because after reading this, it’s hard to imagine modern philosophers tackling such questions as: what is one’s duty to the state and country? What is one’s duty to their parents? What is one’s duty to the gods or God?

A General Overview

Cicero starts by defining what duty is.

Duty has two parts:

The doctrine of the supreme good

Practical rules for daily life

As regards to the supreme good, Cicero mentions that duties will often conflict with each other, which brings up these two pertinent questions:

Are all duties absolute?

Is a certain duty more important than another?

To these questions Cicero adds another classification of duties

Mean duty

A mean duty is that for which a reason can be given for its performance.

Absolute duty

An absolute duty is whatever is “right.”

How we go about knowing what these duties are and how we should perform them, is the subject of the book.

Later on Cicero mentions the four Cardinal Virtues

A full understanding of what is true, that is, the search for truth

The conservation of society, while giving everyman his due and promoting his obligations

A great and noble spirit

Moderation in all things

After providing the basic framework in the beginning of the first chapter, Cicero then proceeds to explain them in more detail.

My Thoughts

As I read through the first book, I appreciated how Cicero organized it in general. He was systematic and thorough in his approach, which made it a somewhat easy read for a philosophy book. One point I noted was in regards to the second virtue stated above, and what Cicero calls “common bonds,” which bind society together. He further divides this into two categories, one being justice, and the other charity or kindness.

The first office of justice is to keep one man from doing harm to another, unless provoked by wrong; and the next is to lead men to use common possessions for the common interests, private property for their own.2

I liked this thought, and how it explains the idea of “common bonds.” Cicero further explains there are three ways in which private property becomes “property.” Reading this made me think of John Locke.

The Three Ways of Establishing Property

By long occupancy

Through conquest

By due process of law, bargain, or purchase

Next there is a beautiful passage that I will quote in whole because it moved me and made me think about our modern individualist culture, and how this might not be the best way to live. Cicero posits:

But since, as Plato has admirably expressed it, we are not born for ourselves alone, but our country claims a share of our being, and our friends a share; and since, as the Stoics hold, everything that the earth produces is created for man’s use; and as men, too, are born for the sake of men, that they may be able mutually to help one another; in this direction we ought to follow Nature as our guide, to contribute to the general good by an interchange of acts of kindness, by giving and receiving, and thus by our skill, our industry, and our talents to cement human society more closely together, man to man.

This passage was thought-provoking to be sure; it also made me think back to the founding generation of this country, and how their ideas of “freedom” and “liberty” have connotations different than how we see these ideas today. The more books I read about the Founding Fathers (this book included) the more I understand this fact. Freedom to them did not mean freedom to do whatever you wanted, for that would be chaos. On the contrary, they understood that freedom came with great responsibility, that is, a responsibility to one’s country, to one’s parents, and to society at large.

What is Justice?

A good quote of the book was this one concerning justice.

Fundamentum autem est iustitiae fides, id est dictorum conventorumque constantia et veritas.

But the bedrock of justice is good faith, that is, steadfastness and truthfulness of promises and agreements.3

Thus, to Cicero, good faith and keeping promises is justice. But how did Cicero define injustice? He saw it in two ways.

Those who inflict wrong on others

Those who do not stop the wrong from happening

Cicero says:

For he who, under the influence of anger or some other passion, wrongfully assaults another seems, as it were, to be laying violent hands upon a comrade; but he who does not prevent or oppose wrong, if he can, is just as guilty of wrong as if he deserted his parents or his friends or his country.

Conflicting duties

When I first read about conflicting duties, I was intrigued to see what Cicero would put in this category.

Promises are, therefore, not to be kept, if the keeping of them is to prove harmful to those to whom you have made them; and, if the fulfillment of a promise should do more harm to you than good to him to whom you have made it, it is no violation of moral duty to give the greater good precedence over the lesser good.

Cicero gives an example of someone promising to represent a client in court (he was a lawyer after all), but by chance his son falls deathly ill and needs to be attended to. This would not be a failure of the lawyer’s duty to break the agreement with the client. In fact, if he to whom he had promised were to become angry at this decision, he would severely lack an understanding of what true duty is.

My Favorite Quote

Summum ius summa iniuria

The greater the laws, the greater the injustice.4

Final Conclusion

There is much more I could give in describing this fascinating first book of Cicero’s On Duties. Reading through it so far has been a pleasure and enlightening. I will need to reread it and continue to read through the next two chapters to get a full understanding of its message and content; however, it has already made me understand why it was so important to Jefferson and others of his time.

Thank you all for subscribing!

My translation.

Translation by Walter Miller.

My translation.

My translation.

Hi, John. That's a real shame. It's crazy to think, we spend years learning a language to read its literature and thoughts, but then to not have a discussion about its meaning is a real tragedy. You can always take it up as a personal goal.

When I was in Latin class in high school, we translated Cicero, Julius Caesar, and Virgil. In all those years we only translated. We never learned to come to grips with the meaning of what we were translating. We were never asked what we thought about these men and their writings. What a wasted opportunity.